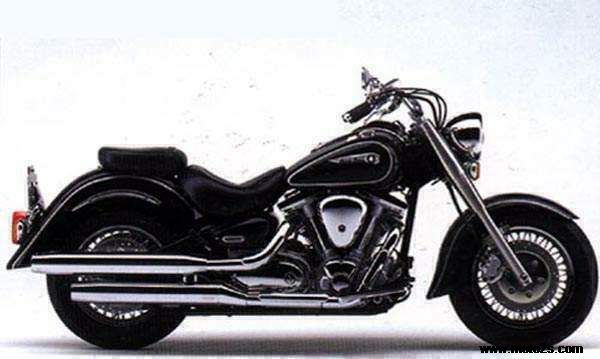

Yamaha XV 1600 Road Star

This was our first test of the Yamaha's new Road Star motorcycle, and we summed it up thus: "Yamaha's new 1602cc V-twin has a lot to love: great power, classic looks and sound, elegant finish, smooth manners, a custom-friendly design, and a price that leaves enough change to make it your own." From the February 1999 issue of Motorcycle Cruiser magazine. It's hard to know where to start with Yamaha's new Road Star. Engine displacement is an issue. So is the configuration of the engine, which some will see as a blatant attempt to copy Harley. Belt final-drive gets people talking too. And how about the price? How did Yamaha build an entirely new engine and motorcycle of this quality and displacement and slip it into such a slim price? Once you ride it though, all those paper issues and imagined controversies fade from your consciousness. This motorcycle looks right, feels right, sounds right, and rides even better. That big motor -- the biggest engine currently built by a motorcycle manufacturer -- exceeded our expectations. And not just for power, but for smoothness, appearance and accessibility as well. Details of its construction appear in the accompanying sidebar, so we'll focus here on how Yamaha's new monster-twin performs. The most remarkable character of this 1602cc V-twin is its massive low-rpm torque. It will literally idle in fifth gear on a level road, with virtually none of what is termed "chain snatch" on a bike with a chain. The massive flywheel effectively smoothes out the power pulses, and though it gets slightly jerky when you open the throttle at that speed, it accelerates willingly, smoothing out completely in just a few hundred rpm. The power simply continues to flow until you hit the rev-limiter at 4200 rpm, and it never gets buzzy along the way. At 60 mph, it is just reaching its 2250-rpm torque peak, where Yamaha claims a massive 99 foot-pounds on tap.

That all translates into effortless departures from a stop, even if you pull away in second gear. Sometimes, while carrying a passenger we did so deliberately, to smooth the departures from stops, even if you pull away in second gear. Sometimes, while carrying a passenger we did so deliberately, to smooth the departure and eliminate one shift. If you pull off in first, you may want to shift to second as soon as the clutch is out. And the first-to-second gear change presents the largest ratio gap in the wide-ratio five-speed. Short-shifting is the rule with this bike, and despite the ultra-overdrive top gear, there is good power to pass traffic with just a twist of the wrist. In our top-gear acceleration tests, it out-performed most big twins, and those that do outrun it (the new Harley, the twin-carb Kawasaki Vulcan 1500 and Suzuki's 1400 Intruder) have a gearing advantage. It also left behind Yamaha's own Royal Star. Probably because of its relaxed, low-rpm gait, the engine didn't seem to be pulling that hard, and we would have guessed it was slower. Tall gearing translates into a relaxed, solid drumbeat from the engine on the highway, and also permits great fuel mileage. We approached 50 mpg during immoderate highway use and averaged 43 mpg overall. Throttle response was smooth and clean, with no abruptness or flat spots. Although it required choke to start in the morning, the big V-twin warmed soon after. Looking at the specifications won't prepare you for the uncanny smoothness of the engine. Unless they have counterbalancers or offset crankpins, twins configured with that 45- to 50-degree V-angle are supposed to vibrate quite a bit. And bigger V-twins should do so with proportionately greater magnitude. But though the Road Star won't fool you into thinking it has an electric engine, its vibration is never intrusive or tiring. Until we were told otherwise, we believed it did use a counterbalancer or at least rubber mounts to isolate the engine. As it turns out, it has neither. Since it is a single-crankpin design, the exhaust beat is classic big twin. And, at least in its American version, there is enough weight to the stock bike's exhaust note to let you know it's armed with some real displacement. Bikes with heavy flywheels tend to lurch away from a stop unless they have controllable, progressive clutches. Fortunately, the Road Star's clutch is flawless. And because it is cable-operated, you can adjust it to fit your hand. We also give top marks to the five-speed transmission, which has a heel-toe shift lever. Shifts are smooth, positive, light and quiet. Despite the extra transmission shaft, there is little lash (i.e., play in the drive line) in the Road Star. The Kevlar-reinforced, final-drive belt is quiet and clean, and requires little attention. The riding position suited most riders well, though as rider height climbed past six feet, the complaints about the shape of the bucket increased. All riders wished for slightly more room rearward, and a turn-up at the back of the saddle that more closely matched the curves of their backsides. (Taller riders asked for it most loudly.) The rider portion of the two-piece saddle is otherwise well-done with good padding and width. Judging from its appearance and the initial feel, we expected it to get old quickly. But it was a few hours before we began to squirm. Smaller passengers who were narrow in the beam adjusted well to the somewhat narrow passenger pad, but it was too narrow for more amply configured back-seaters. Light passengers did say they got bounced around a bit. We point the blame for that at a slight shortage of rebound damping in the rear shock. Both ends are on the firm end of the spectrum, but only big, sharp bumps came through harshly enough to affect the rider. All riders praised the relationship of seat to the floorboards and handlebar. At 33 inches from tip to tip, the handlebar was wide enough for confident control in town, but not so wide as to make you a sail in the highway. Moderate rise and pullback means most riders had to barely lean forward to reach it comfortably. The wind's blast wasn't broken by the headlight as much as some other bikes, but it wasn't oppressive either. We have two schools of thought around here about what braking characteristics are desirable. One likes brakes that have a strong initial bite, offering the quickest response in a panic stop. The other prefers brakes that take fairly heavy pressure before they lock up. The latter school was more comfortable with the dual-disc front brake on the Road Star. The dual-rotor front brake serves up plenty of power, but a solid squeeze is needed to get it all. Fade was not a problem. The rear brake offers the best pedal location of any of Yamaha's floorboard-equipped cruisers to date. Power and control are also good. Low-speed handling is very controllable and predictable. The handlebar isn't too wide, or pulled back so far that it crowds you or makes you stretch during full-lock turns. The 27.9-inch-tall saddle provides a comfortable reach to the road, and the floorboards are out of your way when your feet are down. The bike carries its weight low enough to feel quite manageable when you are pushing it around at a stop. And that light, low-effort feel remains when you get moving. Cornering is limited by clearance, which feels comparable with the Royal Star; which is to say, on the low end of the scale. The fold-up floorboards drag first and loudly, giving plenty of warning that you are reaching the limit. The biggest danger is some riders will be alarmed, straighten up and run off the road. In fact, the bike is in control and has some available lean-angle in reserve before anything solid touches down. Despite rubber mounts, the bar feels well-connected to the steering. Steering is neutral at high and low speeds, with no tendency to tip into a corner and little propensity to straighten up if you brake in a corner. In faster corners, the rear end pumps a bit if you make steering inputs midcorner, or hit a bump -- especially with a passenger. Stability is fair. If we gave the bar a big shake when riding down the road, the Road Star would oscillate about a cycle longer than we would normally expect, though it didn't seem prone to initiate a wobble on its own. Some of the things that unsettle other bikes (parallel grooves, a series of bumps, etc.) didn't wiggle the Road Star. The bike is finished in the general manner of the Royal Stars, which is to say, first class. In fact, the flangeless design of the tank actually raises the standards a bit. Many components -- such as the taillight and brushed-finish, stainless steel fork covers -- appear to have been lifted directly from the Royal models. The deep fenders and tank shape bear a clear family resemblance, but pieces like the large headlight bezel give it its own character. The single rear shock is tucked out of sight and controls the hardtail-look swingarm via a linkage. Polished covers for the brake rotor hubs are a welcome touch. A few items drew criticism. The cover over the final drive pulley was termed "tacky," "weird," "out of place," or just plain "kinda ugly." The front of the engine is a bit cluttered by dual horns (though their attention-getting volume does make them welcome), rear-brake master cylinder, and spin-on oil filter. Some of the engine's external plumbing begs for stainless steel replacements. Doubtlessly there will be aftermarket remedies for many of these complaints. At the bike's introduction, Yamaha showed heavily customized bikes. It says it has 160 accessory items already available, including chrome, saddles, saddlebags and windshields. We also saw cast wheels, headlights, pipes and other pieces from aftermarket vendors. Most of these accessories should be available now. The bike hit dealers in December, with the Silverado version a few weeks behind. Customizing should be easy; the bike was built with modification in mind. You won't encounter hidden roadblocks to changes every time you take off a cover or remove a component. The design is exceptionally straightforward. We found a raft of well-thought-out details. Placing the dipstick/oil-filler under the locking saddle might foil someone bent on sabotage. (The editor was once called to testify in a case where a neighbor had apparently put grass clippings in a motorcycle's oil filler.) The fork, ignition and saddle unlock not only with the same key, but the same lock. Located conveniently in front of the tank-top speedometer, the ignition lock is positioned to operate as a fork lock, and also operates the seat lock via a cable. Lugs on the bottom of the triple clamp allow use of a padlock for additional security. The technology Yamaha used for the instruments makes the entire gauge and light-cluster less than a half-inch-deep, reducing the amount of fuel space needed to accommodate it. The needles for both analog instruments, the speedometer, and fuel gauge operate by step motors; they calibrate themselves when the ignition is turned on by swinging to full-scale readings before returning to zero and the current fuel level. The LCD display in the speedo face has a two-line display. The top line is a clock, and you can toggle between the odometer and two tripmeters on the second line. Mounted in a pretty chrome setting and nicely backlit with large markings, the instruments' only drawback is their position, which is well below your line of sight. Priced at $10,499 for the base model and $11,999 for the Silverado model, the Road Star's price suggests it is a second-tier machine compared with the Royal Star. We don't know about long-term reliability yet (we are working on it), and the Road Star only has a one-year warranty (rather than the Royal Star's five years, plus roadside assistance), but in all other standards of measurement the Road Star is The Star among Yamaha's cruiser line. More than that, the Road Star raises the bar for everyone, and not just in displacement. ABOUT THAT ENGINE... After sitting through many presentations for new models, you get a feel for what a difficult conceptual leap the classic American cruiser engine must be for Japanese engineers. For those raised on innovation, technical excellence, reducing mass and improving performance, wrapping your thoughts around the comparatively low-tech or even retro-tech requirements of an ideal cruiser motor must be demanding. And that makes Yamaha's new 1600cc V-twin that much more remarkable because -- unless it reveals some reliability flaw -- it is, in our opinion, the standard against which all other big V-twins will be measured. The 1602cc engine is more than just the biggest OE engine on the market. It is straightforward like an American design, but it also enjoys traditional Japanese engineering and attention to detail. The prominent finning is genuine and necessary, since the engine really is air-cooled. There are no extra covers to accentuate the size of part of the engine. The big triangular airbox really is an airbox, and the entire airbox is there. About the only unconventional piece is the dipstick tube, which projects up from the sump above the transmission's output shaft. The side panels hide it. To reach it, simply pop off the saddle. It's been a long time since a new Japanese engine came with pushrods. How did Yamaha arrive at such a low-tech system of valve actuation? Styling, we were told. Those fat chrome pushrod-housing tubes highlight the 48-degree V-angle. Both pushrods for each cylinder live inside the single tube. They rest on hydraulic adjusters. At its top, each pushrod operates a rocker on the end of a shaft. The other end of the shaft has two integral rockers to depress the two intake or exhaust valves for that cylinder. One of each pair of rockers has a threaded adjuster. That permits adjustment for any difference in manufacturing tolerances or wear. An automatic decompression system lifts one exhaust valve to make things easy on the starter motor. The combustion chamber has a pentroof configuration with two spark plugs. The single 40mm carb has a throttle-position sensor and accelerator pump. One of the attractions of pushrods is that they keep the engine short from top to bottom. Indeed, Yamaha claims that despite its ultralong 113mm stroke, the 1602cc engine, at 21.1 inches tall, is the shortest big twin available. One sign of its Asian roots is the 97.76-cubic-inch displacement, which stops just 37cc shy of 100 cubic inches. An extra 2mm added to the 95mm bore would have given Yamaha's copywriters one more thing to brag about, but the displacement target was seen in metric terms rather than American. Since the cylinders feature low-friction, high-heat-transfer, ceramic-composite liners over an aluminum base, overboring won't be easy. Some will see the 48-degree V-angle as an effort to mimic Harley. But this engine is much smoother than any 45-degree Harley twin, so you can't argue with the design decisions. In fact, the most amazing thing about this engine is how smooth the bike is without counterbalancers or rubber engine mounts. No doubt the tremendous mass of the crankshaft (a hefty 45 pounds) helps smooth it out, and the engine is a long way from the handlebar.

Yamaha feels confident enough with the deep head fins and ceramic-lined cylinder that the bike has no oil cooler cluttering up the engine bay. The spin-on filter at the front of the engine is a bit obtrusive, but it's also easy to reach. Although the engine is short from top to bottom, it's extra long front to rear, partly due to the fact that the transmission has an additional shaft behind the two standard transmission shafts. Power leaves the left end of the crankshaft through a geared primary and wet clutch. It exits the five-speed transmission on the right side, where a silent chain and another reduction carries it back to that third shaft which runs across to the drive pulley for the belt final-drive. This final shaft not only puts the belt on the left side, it also moves its drive pulley rearward near the swingarm pivot. As a result, there is little change in belt tension as the swingarm pivots up and down. Termed a semi-dry sump design, the lubrication system carries the majority of its oil in the crankcase, but there is an additional sump occupying the case above the final output shaft. This is where oil is added and its level is checked. Yamaha has demonstrated its vision of what a high-end cruiser can be with the quality and finish of the Royal Star. With its new V-twin it combines that vision with an engine that epitomizes what many people feel a cruising motor should be -- in style and performance. Art Friedman |

1999-01年Yamaha XV 1600 Road Star

2013/8/2 14:53:00